- Article Summary

-

Introduction

The global automotive industry is undergoing the most disruptive transformation since the invention of the assembly line. As the world moves toward a low-carbon economy, electric vehicles (EVs) are no longer niche products but the backbone of future mobility strategies. Governments are setting ambitious phase-out dates for internal combustion engines (ICE), investors are demanding credible climate transition plans, and consumers are increasingly aware of the environmental footprint of their choices. This tectonic shift, however, is both technological and organizational, reshaping how automakers measure and disclose their impacts.

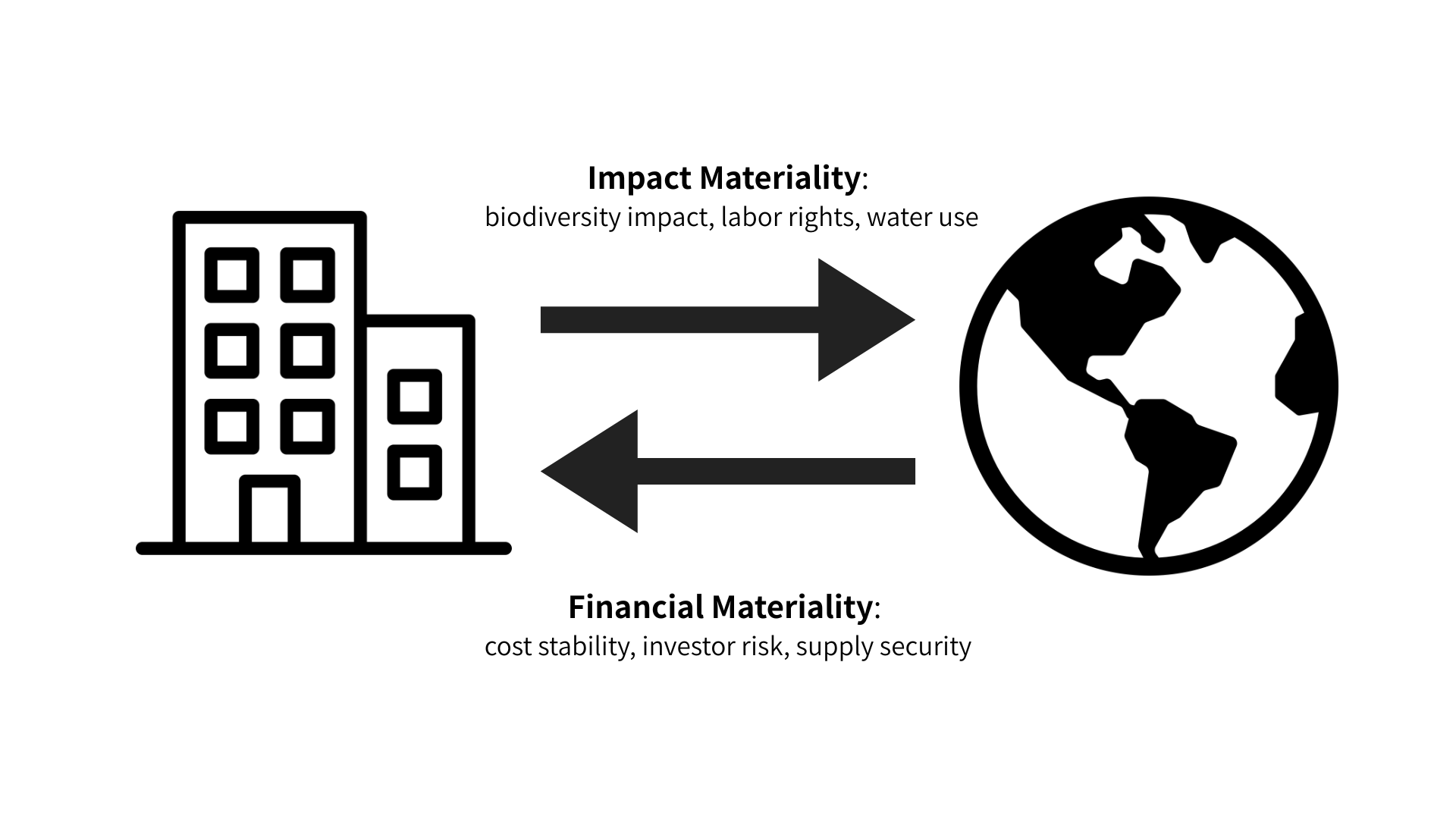

At the center of this evolution is the concept of double materiality. Unlike traditional financial materiality, which assesses only the risks and opportunities that external factors pose to a company’s profitability, double materiality also requires an understanding of the company’s own impacts on people, society, and the environment. For automakers, this means not only calculating the cost of climate policies or resource scarcity but also accounting for how vehicle production, supply chains, and usage patterns affect communities and ecosystems worldwide. In practice, double materiality is emerging as a strategic compass for the EV transition, shaping regulatory compliance, corporate governance, and market competitiveness.

Regulatory and Market Drivers of Double Materiality in the Auto Sector

The push for double materiality is largely regulatory in origin, but market forces are amplifying its importance. In Europe, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) has redefined corporate disclosure by making double materiality a legal requirement. Companies, including global automakers operating in the EU, must now disclose both how sustainability risks influence financial performance (financial materiality) and how their operations affect society and the environment (impact materiality). For example, a German automaker selling cars in the U.S. still needs to account for biodiversity impacts linked to cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo if those activities are tied to its EV supply chain.

Similarly, the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) extends obligations beyond reporting to proactive risk management, compelling automakers to address human rights and environmental harms across supply chains. In the U.S., the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) emphasizes domestic sourcing and environmental safeguards for EV batteries, indirectly embedding double materiality by linking subsidies to both economic competitiveness and sustainability outcomes.

Financial markets are reinforcing these regulatory frameworks. ESG rating agencies, investors in green bonds, and climate-aligned indices now demand evidence of double materiality assessments. Automakers that fail to disclose their broader societal and ecological footprint risk exclusion from major investment portfolios. This trend reflects a deeper market logic: long-term value creation in the auto sector depends as much on societal license to operate as on quarterly profits.

Table 1. Examples of Double Materiality Risks for Automakers

| Dimension | Financial Materiality (Outside-in) | Impact Materiality (Inside-out) |

|---|---|---|

| Climate Change | Higher carbon costs, stranded ICE assets | Reduced GHG emissions through EV adoption |

| Supply Chains | Price volatility in critical minerals | Deforestation, biodiversity loss, labor rights concerns |

| Consumer Trends | Market shift toward zero-emission vehicles | Improved urban air quality, equitable mobility access |

| Regulation | Compliance costs with CSRD, CSDDD, IRA | Increased transparency and accountability |

Supply Chain Sustainability and Critical Minerals

One of the most pressing arenas for double materiality is the EV supply chain. EV batteries require substantial amounts of lithium, cobalt, nickel, and rare earth elements. Financially, these resources represent both opportunity and vulnerability. Supply disruptions from geopolitical tensions, such as resource nationalism in Latin America or export controls in China, can destabilize production schedules and raise costs. Commodity price swings also affect profitability, as seen in the sharp fluctuations of lithium carbonate prices between 2021 and 2023.

On the impact materiality side are the environmental and social consequences of mineral extraction. Cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo has been linked to hazardous child labor conditions, while nickel extraction in Indonesia has contributed to deforestation and water contamination. Local communities often bear the brunt of these impacts, which can erode automakers’ reputations and trigger NGO campaigns or legal action.

In response, leading carmakers are adopting responsible sourcing strategies aligned with OECD guidelines, the Global Battery Alliance’s Battery Passport, and blockchain-based traceability systems. Some have invested directly in mining projects with stricter environmental standards, while others have entered long-term supply agreements tied to sustainability performance. These steps illustrate how double materiality translates into concrete action: ensuring secure and cost-effective mineral access while actively addressing ecological and social harm.

Lifecycle Emissions and Circular Economy Integration

While EVs reduce tailpipe emissions, their lifecycle emissions story is more complex. Battery production is highly energy-intensive, often relying on electricity grids that are still carbon-heavy. Studies show that producing an EV battery can emit up to 70% more CO₂ than manufacturing a conventional engine vehicle. Financially, this creates risks if lifecycle emissions undermine the climate credibility of EVs, potentially prompting stricter regulations or weakening consumer trust.

From the impact materiality perspective, lifecycle impacts extend beyond carbon. The water intensity of lithium extraction, waste generated during battery manufacturing, and the lack of recycling infrastructure pose long-term environmental challenges. Here again, double materiality requires automakers to view lifecycle emissions both as internal financial liabilities and as external social and ecological costs.

Automakers are increasingly investing in circular economy strategies. Recycling facilities for lithium-ion batteries are being scaled in Europe, North America, and Asia, aiming to recover critical minerals and reduce dependence on virgin extraction. Some companies are exploring second-life applications for EV batteries in grid storage, prolonging their useful life and lowering total lifecycle emissions. Renewable-powered gigafactories are another step, with companies like Tesla and Volkswagen pledging carbon-neutral battery plants by 2030.

Table 2. EV Lifecycle Double Materiality Assessment

| Lifecycle Phase | Financial Materiality (Outside-in) | Impact Materiality (Inside-out) |

| Mining & Refining | Supply risks, commodity price volatility | Deforestation, water use, community displacement |

| Battery Production | Capital intensity, potential regulatory penalties | High carbon footprint, local air and water pollution |

| Vehicle Use | Revenue from EV adoption, customer loyalty | Reduced air pollution, access to sustainable mobility |

| End-of-Life | Recycling cost savings, circular business models | Reduced e-waste, recovery of critical materials |

Conclusion

The transition to electric mobility is a profound restructuring of how automakers create, measure, and report value. Double materiality provides a framework that captures the full complexity of this transformation. By requiring companies to assess both the outside-in risks to financial performance and the inside-out impacts on society and the environment, it ensures that decision-making aligns with long-term sustainability.

Regulations such as the CSRD and CSDDD make double materiality a legal requirement, while market expectations turn it into a competitive advantage. Automakers that embed this framework into supply chain governance, lifecycle emissions strategies, and circular economy models are more likely to thrive in the EV era. They not only mitigate risks and secure investor trust but also contribute meaningfully to global climate and social goals.

In the end, the automakers that succeed will be those that see double materiality not as a compliance burden but as a strategic opportunity. By balancing profitability with responsibility, they can drive the EV revolution in a way that benefits both shareholders and society at large.

Why Work with ASUENE Inc.?

Asuene is a key player in carbon accounting, offering a comprehensive platform that measures, reduces, and reports emissions. Asuene serves over 10,000 clients worldwide, providing an all-in-one solution that integrates GHG accounting, ESG supply chain management, a Carbon Credit exchange platform, and third-party verification.

ASUENE supports companies in achieving net-zero goals through advanced technology, consulting services, and an extensive network.